INTRODUCTION

This article is about a simple and effective technique for getting the best sound out of your tango recordings. More specifically, we are targeting the electric recording era, from 1926 to 1949. The technique defines a set of simple rules which allow to obtain repeatable results in any tango venue, on any recording, with minimal adjustments between the tandas. It was initially tried and tested in several milonga venues in Toronto in 2014, and further improved with the feedback from the DJs from all over the globe. I strongly believe that it can dramatically improve your sound, and, at the same time, you would spend less time tweaking the equalizer, cursing the bad recording and/or inadequate sound system, etc.

This article is about a simple and effective technique for getting the best sound out of your tango recordings. More specifically, we are targeting the electric recording era, from 1926 to 1949. The technique defines a set of simple rules which allow to obtain repeatable results in any tango venue, on any recording, with minimal adjustments between the tandas. It was initially tried and tested in several milonga venues in Toronto in 2014, and further improved with the feedback from the DJs from all over the globe. I strongly believe that it can dramatically improve your sound, and, at the same time, you would spend less time tweaking the equalizer, cursing the bad recording and/or inadequate sound system, etc.

I will not provide any “before and after” sound examples – the technique is entirely yours to try at your venue, to improve, to use or to lose. Feel free to let me know whether you like it or not in any form.

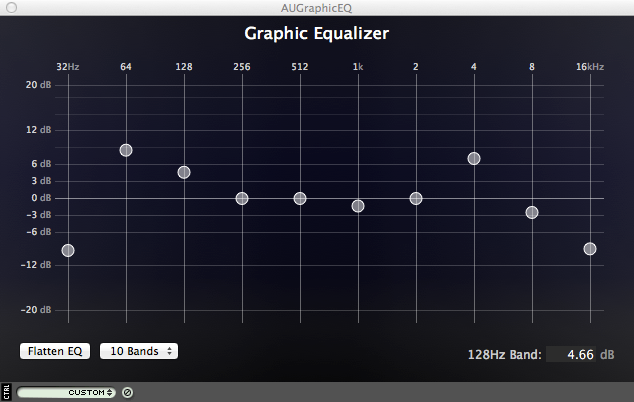

In order to try this technique all you need is a 9 to 10 bands graphic EQ with 12 dB boost and cut, either in software, like this one:

… or in hardware, like this one:

Please, do not use EQ in iTunes – its incredibly slow response time will prevent you from clearly hearing the differences in your experiments.

Also you will need either a pair of high quality DJ headphones, or, better yet, an hour of time to yourself and your music at the venue where you regularly DJ, before the milonga. In my own experience, using home sound system, be it a Walmart bookshelf audio or British hi-end system alike, is grossly inadequate for this kind of experiments. If you don’t have a 10-bands EQ, scroll down to the section with the advices on various types of EQ to try.

In order to convey this technique in a reasonable amount of space, I will not try to prove each and every statement here, as you can (and should!) test it all for yourself.

A FEW MYTHS OF TANGO DJ

- There is nothing useful either below or above the mid-range on the shellac – wrong.

- There is no cure for reverberation – wrong.

- If you equalize out the groove noise you will inevitably lose the musical content with it – wrong.

- A “smile” on the EQ is a sign of a clueless DJ – partially true… but… keep reading

SOME BASIC FACTS FIRST…

It is generally accepted that human ear can distinguish the sounds spanning from 20 Hz to 20 kHz. To put it into perspective, the lowest note on the piano, A0 registers at 27.5 Hz and the highest, C8, at 4186 Hz. The huge range between the 4.2 kHz and 20 kHz (over two full octaves) is responsible not for the musical tones, but for their character, such as timbre and shape.

The graphic equalizer with one octave spacing contains 9-10 bands within the human hearing range, which are conventionally set at 31 or 32 Hz (10-bands only), 63 or 64 Hz, 125 Hz, 250 Hz, 500 Hz, 1 kHz, 2 kHz, 4 kHz, 8 kHz and 16 kHz. There is no particular note corresponding to this sequence of frequencies, but the closest one would be B. So you can imagine that your EQ is “tuned up” to B0, B1… up to B7, and then have two more bands above for the timbre control. The boost/cut range for each band is usually either 6 dB or 12 dB.

Subjectively, human ear perceives the 10 dB change in the signal level as “twice as loud”, and 1 dB change as “barely perceivable”. In order to follow our examples, your equalizer should have all the bands, and be capable of 12 dB cut and boost. Our ears very quickly adapt to the changes in the sound, so if it only seems to you that you hear the difference when you run the experiments, always compare your new EQ setting with flat setting, by using IN/OUT button on your EQ (it might also be called ON/OFF on a software EQ or BYPASS on some hardware EQ). If your EQ does not have such button – find another EQ. I am not kidding. Better software EQ also provide A/B button – to switch between your previous and current setting, which comes very handy for comparison of finer adjustments.

Also, the human ear has highly non-linear response to the extremes of the sound spectrum, namely, at low volumes we hear the mid-range much better than extreme lows and highs. This, together with the non-linear response of home equipment, led to ubiquitous “smile” on home EQs – on low volume the music indeed sounds better with the “smile” than without it. Thus, when you run your own tests, do play it loud… not at the levels of a local dark rave club, but at the levels, comparable with your normal sound level at your milonga. Otherwise, you simply may not hear a pronounced effect.

The electrical recording on shellac, which we will simply call “the recording” is capable of holding an astounding range spanning from approximately 30 Hz to 7 kHz. That is, this range covers full piano scale, and leaves almost a full octave for the timbre variations. Such a wide range may come as a surprise to you, but there is an explanation why, without proper equalization we never hear it in full. You see, the recording amplifier was intentionally set to gradually cut the recording level of all the frequencies below 250 Hz, and also above 5 kHz. The cuts were needed for several technical and economical reasons, but then the better gramophones themselves would mechanically “amplify” the lower range thus partially bringing back the loss, created at the recording time. Here is a frequency profile of a typical recording amplifier of the 30s:

Much more intriguing details on the process associated with the shellac recording and production can be found in the online reprint of Defects in Gramophone Records article published in 1931, and much more detailed treatment of various shellac recording curves and standardized vinyl recording curve is given in the excellent, modern Disc Recording Equalization Demystified article, but for our purposes of expanding the frequency range of the music that we play, the above figure is sufficient.

The groove noise, or the “hiss” is mostly pronounced on 7.5 kHz band, which gives us a clear hope of isolating the noise from the music, given the appropriate tools.

GETTING ACQUAINTED WITH YOUR EQ

Let us keep the previous drawing handy – it holds a few clues to effortless EQ. Firstly we will simply try and “reverse” it, as the better gramophones did in the Golden Age. Play your favorite tango with a vocalist from the early 30s. Play it in the loop, all the same one, until we are done with our reversals.

We will start with the bass region. Bring up the 63 Hz band to full 12 dB, 125 Hz to about 8 dB and 250 Hz to about 4 dB. Press in/out button. You will undoubtedly hear a substantial bass boost. If it is way too much, use 9 dB, 6 dB and 3 dB values instead, and press in/out again. Better? Good! Now, bring 250 Hz back to zero and 125 Hz just slightly up from its previous position. Compare the sound with all three sliders up to the sound with only two sliders up. Chances are, that if you hear the difference, the setting with two sliders will appeal more to you – in this setting the bass is more pronounced and, at the same time, the sound is less muddy. If you do not hear the difference, try this – set all three bands at the same level around +6 to +9 dB, for a substantial increase in you bass line, and then bring the 250 Hz slider down, to 0 dB. Now you should clearly feel the “muddiness” added by the upper slider. Remember not to use 250 Hz slider in bass adjustments (the older gramophones did not – their mechanical EQ boost would start at about 150 Hz).

Note that you might stumble across an occasional tango (there are few well known ones from OTV repertoire) with the bass boost added when the CD transfer was prepared. Also, newer Golden Edition TangoTunes transfers have a very satisfactory frequency range, which require only minimal bass adjustments. And, finally, the club-like sound systems usually have over-boosted bass line.

In such case simply use lower initial values, say +4 dB and +2 dB. While the principle is still the same, but your own ears are, of course, the best judge for the actual amount of boost or cut for any of the frequency bands under the discussion.

If you are experimenting in your milonga venue, and have 31 Hz band on your EQ, raise the 31 Hz slider all the way up. You will hear lots of unpleasant low-frequency rumble. If you are using headphones, most probably, nothing will change at all, since headphones are incapable of producing frequencies that low in the spectrum. Now, bring the 31 Hz slider down, to about -3 dB to cut the rumbling and to ease the load on your speakers and power amplifier. Remember to cut the closest to 30 Hz frequency band when boosting the bass.

Now, let us move to the treble region. You can see on the diagram that this region is between 5.5 kHz and 7 kHz. On our 10 bands EQ we do not have such a band, so the closest one to use will be 4 kHz band. Bring it up about 6 dB. You will hear an increased amount of groove noise, but also you will hear how much your sound has brightened up. Ignore the hiss just for a moment. Try in/out and compare the sound. Move the slider slightly up and down. If you overshoot your settings, your sound will become too thin. Also, if you have an estibillista in your tango, you will hear that at too high settings his voice may become quite unpleasant. When you are satisfied with the settings, using in/out button, keep it and move on.

Now, it is time to get rid of the groove noise. First, bring 16 kHz slider down to -9 dB, as there is no useful signal there, anyway. The groove noise will somewhat decrease, and the overall sound will become softer. Keep this slider at -9 dB and don’t touch it anymore. Now move up and down the 8 kHz slider. You will immediately notice that this slider is a perfect control for the noise, and, at the same time, even at deep cut positions (down to -8 dB or so) your musical content is still there, untouched. Find a perfect position for 8 kHz slider. If your track contains a lot of groove noise, try even deeper cuts on 8 kHz slider, followed by bringing up the 4 kHz slider. Only in the worst cases the 4 kHz slider should be brought down to 0 dB. Most of the time the 4 kHz slider should be up, opposite to 8 kHz. Remember to decrease the amount of cut on 8 kHz slider after your particularly noisy tango has finished.

Note that we already twice used the “scissors effect” on the EQ. First, we would cut the frequencies below 30 Hz while giving the extreme boost to the frequencies above 30 Hz. Next, we used the same trick again with the groove noise. Remember those scissors when attempting extreme adjustments on the bass and on the hiss alike.

Well, we are almost there. Now, stop the track that you were playing, engage OUT button, and play the next track in your tanda, for about 30 seconds, without the EQ. And then – engage the EQ again. Do you hear what I hear? Do you like the result? Good! Now try to very slightly adjust the 63 Hz / 125 Hz sliders to add/remove some of the bass, the 4 kHz slider to increase/decrease brightness and the 8 kHz slider to cut more or less of the groove noise. Do not touch any other sliders. They are out of the picture, at least for now. Less is more.

While you are enjoying the rest of your tanda, let me make an observation about the groove noise. There is a big difference between the groove noise which is inherent to every shellac plate and the clicking sound which occurs because of the scratches and dents on the surface. The former can be precisely targeted with the 8 kHz slider, while the latter cannot. Sometimes, there is so much of the clicks (“Mi vieja linda” immediately comes to mind), that they can be mistaken for the groove noise. However, the clicks can be only removed manually, offline, or with some advanced processing plugins online. If there is an excessive amount of groove noise, lowering the 4 kHz slider to 0 dB and 8 kHz slider to -12 dB, usually helps, although at the expense of the high frequency content, but the clicks and scratches would still be there, whatever you do with 4 kHz and 8 kHz sliders.

Try in/out again, and stop your music. Then, reset all your sliders back to 0 dB positions for the last experiment.

Now we need a vocal track from the mid-40s, with an excessive amount of reverberation, carelessly added by the engineers, when preparing the CD transfer. May I suggest you to use a Miguel Calo / Raul Beron tanda? Start playing the tanda, and pay attention to the reverb. Now, move 1 kHz slider steeply up, to +6 dB. Do you feel that the reverb became unbearable? Good! Now move the same 1 kHz slider down, to a modest -3 dB position. Try in/out button. Do you feel that even a slight adjustment of 1 kHz band successfully cuts our perception of the reverb? Try higher and lower cuts, but now paying attention to the overall quality of the music, not only to the amount of reverb. You will undoubtedly feel that with this slider “less is more”. Too big cuts on 1 kHz create really creepy effects. Don’t do it. Use it moderately and only when required by the source material.

Note another EQ trick that I just used – when we were looking for a frequency to CUT, I’d ask you to boost it first. Our ear responds to boosts better than cuts, please, remember this, when making your own EQ experiments, and, if you are still not convinced that 250 Hz band should be left alone when boosting the bass, try the trick on this band.

Now bring the 1 kHz slider back to 0 dB, cut -3 dB at 31 Hz and -9 dB at 16 kHz. Then adjust your bass up (63 Hz and 125 Hz, the 63 Hz is always proportionally higher than 125 Hz), your brilliance (4 kHz slider) and your hiss (8 kHz slider). Chances are that your new setting will be quite similar to the previous one, for the 30s tanda, maybe just a touch less extreme than before. Try in/out button again. Do you feel that there is just a bit less reverb, even though your 1 kHz slider is at 0 dB position? Now, cut the reverb, by just slightly moving 1 kHz down… and enjoy the rest of the tanda.

This is how my EQ curve looked like in one of Toronto milongas venue. Could you guess the reasons for the differences between my suggestions above and the actual curve? Just by the look of the curve, could you tell if the tanda that I was playing had lots of groove noise?

“CUATRO COMPASES” OF TANGO DJ

Let us formalize our findings. There are four major characteristic areas of the the shellac record, namely, BASS, REVERB, BRILLIANCE and HISS. And there are also two extreme regions beyond those four.

Note that the boundaries of these regions are not exactly the same as the frequencies on the 10-bands EQ!

0. ULTRA-LOW MUD: low-cut all the frequencies below 30 Hz. Don’t let these ultra-lows to destroy your music and overload your equipment. Set it once, and forget about it.

1. THE BASS: Give a liberal, yet gradual boost to the range from 150 Hz down to 30 Hz, with a highest peak at 30 Hz. Give your music lots of deep, solid foundation. Help the beginners and delight seasoned tangueros. But don’t muddy up your sound, do not boost anything above 150 Hz!

2. THE REVERB: Slightly bring down the 1 kHz band. Just a few dB is sufficient to significantly cut the excessive reverberation, be it a natural echo, or an artificial one. Reverse-engineer bad sound engineering, but don’t overdo it! Also, don’t forget to bring it back to zero at the beginning of the next tanda. The reverb control should not be used when there is no objectionable reverb to cut.

3. THE BRILLIANCE: Liberally raise the 6 kHz band. Add some sparkle to the music! Don’t worry about the groove noise just yet, we will fix it in the next step.

4. THE HISS: use your shelving 7.5 kHz band as the groove noise control. Move it down as much as needed. Your brilliance control will save your day and your music.

4′. THE ARTIFACTS AND HISS: High-cut everything above 10 kHz – there is no music, but there are plenty of mp3 compression artifacts, D/A conversion artifacts, and similar goodies that better be kept under the table. Also, high-cut filter helps to deal with extreme groove noise on fashionable Golden Ear Edition transfers from Tango Tunes.

Now, we have reduced the 10 bands EQ to four regions with two extremes. Do not use any other bands on the EQ, except the ones that we have mentioned. Our goal is to consistently get the best sound, track after track, with the minimal movements of the EQ controls.

This is how our perfect TJ EQ curve would’ve looked like, if, instead of 10 band EQ we would use precise 31 band EQ:

… but, of course, using that many bands in live milonga settings would not be very practical, would it?

At this point I’d like to emphasize again that this technique is only adequate for the recordings from 1926 to 1949.

NOTE ON THE 50s RECORDINGS: With the introduction of U47 microphone, magnetic tape masters, vinyl LPs, and RIAA equalization the frequency range of a record moved to 20 Hz – 20 kHz range, so the simplest way to play it is to keep your EQ flat. If you still want some adjustments, you can slightly cut or boost bass and/or minimally cut reverb with the same technique as described above. However, the brilliance band is now somewhere around 10-12 kHz, while the 16 kHz band should be kept at 0 dB, without any cut. Also, there isn’t, indeed, any simple EQ technique to remove the LP hiss while preserving the musical content. The hiss can be only removed at the expense of the music by experimenting with the frequencies bands higher than 8 kHz. Ironically though, Di Sarli recordings of 1951-1953 with TK / Music Hall are of so bad quality that you might be better off using the 40s technique on them.

Also, when applying “liberal EQ”, especially in the lows, always keep your eye on the levels meter, and your ears on the possible distortions from the speakers – this low boost does not come for free, and if your PA is already at its limits, do lower the EQ output level, the mixer channel level, and/or the mixer mains level.

Also, you might have heard or read somewhere that “cutting is better than boosting”. I do not argue against this, indeed useful rule, and even tried, with several EQs to bring down the whole curve, so that the middle frequencies were always cut, while highs and lows would not require such extreme boosts as I recommend above. Yet, in my own experience, I would not justify the necessity to move each and every band for any adjustment by a rather marginal, if any, improvement in the sound quality. However, if you prefer to strictly observe the “cutting” rule, you can do exactly that – lower all the sliders to about -3 dB, and then boost the needed ones relative to your new baseline.

And finally, remember that “with too much EQ you can upset the delicate balance of the nature and/or screw up things royally”, as friendly folks from Mackie keep reminding us in every mixer manual. After setting the perfect EQ, try to back off just a little and see if this new setting is still good. When you get a hand on this technique, dialing an appropriate amount of boost and cut will became almost automatic.

Congratulations, you’ve made it! Now take your EQ and go to amaze your crowd with your the newly found sound. The rest of the article can wait.

QUEST FOR A PERFECT EQ

So, if it is all that simple, why there is even need for a graphic EQ? Maybe there is some 4-knobs EQ with the bands perfectly set for us? Well, let’s see.

Brief look at DJ and PA mixers

My Traktor Pro 2 has emulations of five or even more various DJ EQ. All of them are asymmetric, meaning that they all provide huge cut and reasonable boost, and yet, each of them miserably fails, because of grossly misplaced (for tango DJ purposes!) frequencies bands.

To wit, the four-bands emulation of revered XONE:92 provides low-shelving at 250 Hz, which is way too high – lots of “mud” is added when this knob is boosted, mid-low peak at 350 Hz which is just useless, mid-high peak at 2.5 kHz, which is a half-way between reverb control and brilliance control, and high shelving at 10 kHz, which seem to be OK just by numbers, but quite inadequate when actually used.

Another well known model, Pioneer DJM-600 provides three bands placed as follows: low shelf at 70 Hz – good enough, mid peak at 1 kHz – perfect reverb control and high shelf at 13 kHz. Strangely enough, 13 kHz high band in Pioneer sounds much better than the same band in XONE, but we still miss the brilliance control, and this one is very important, especially when cutting the noise. Also, both of them lack the 30 Hz low-cut filter. Another Pioneer, DJM-800 is very similar to the previous model, while the Classic, Z-ISO and NUO models all sound really bad on tango recordings.

Now let us look at the mixing boards – may be we could find some luck there? Indeed, my favorite Mackie ONYX 1640i has a four-band EQ on each of its channels, with two mid bands having a sweepable frequency control. The high shelving is set at 12 kHz – this is way too high, but it cuts deeply, and we still have the brilliance knob, so this 12 kHz is actually quite useful. The mid-high has a range from 400 Hz to 8 kHz, so we set it at the desired 5.5 kHz. The mid-low has a range between 200 Hz and 2 kHz, so we set it at 1 kHz as reverb control. The low shelving band is at 100 Hz… well, it’s OK, but the low cut filter is set at 75 Hz with 18 dB/octave cut, which is perfect for the mikes but almost useless for us, unless you engage it together with rather steep bass boost. Yet Mackie channel EQ is pretty close to be a perfect TJ EQ.

The four-band channel EQs are rather rare, though. More often you would see a three-band EQ with fixed mid-band, which would not be adequate for our purposes. But if your are lucky to have the mixing board even with a single mid-sweep band going up at least to 4 kHz, forget the pathetic Tape-In connector, and start using the channel strip instead. Also, as an alternative to a channel EQ, look at the master section of your mixer – you might be lucky to find a decent 10-band graphic EQ right there, like on this Behringer mixer. If you are still intimidated by the sheer number of controls on the house mixer – read the Mackie manual. Even if you have another mixer at your milonga – still read the Mackie manual. It is highly entertaining and quite informational as well, in the stated order.

Stand-alone graphic EQ

Now, after you have read the Mackie manual, got over the “turd polisher” knob and “had a frosty beverage”, let’s go back to stand-alone equalizers. Firstly, there are two reasonably priced mini graphic EQ, namely:

They would do the job without doubts, I’ve used the Behringer to run through all the experiments, but their build quality may raise some concerns. If you are looking for a professional grade, rack-mounted model instead, there are plenty, but with a catch – most, if not all of the rack-mounted models are either 15 or 31 bands. While more bands obviously allows for more precise control, you would also have to move more sliders at a time. If you want my advice – 15 band, in mono, is much more adequate for the task at hand than 31 band.

In the world of software EQ, there is plenty of free offerings found at these links:

We will discuss how to install an equalizer plugin at the end of this section.

Introduction to parametric EQ

So, the perfect TJ EQ does not exist, and we would have to resort to graphic EQ? As a matter of fact, it does, but in a form of a parametric equalizer. The parametric equalizer is like a Mackie channel EQ on steroids – it has three to four bands, plus optional high and low cut filters, and on each band you would have two or three controls – boost/cut knob, the sweepable frequency knob, and also the knob that lets you make the band itself wider or narrower. In audio engineering parlance this last control is called “Q” (as in Star Trek Next Generation).

This is how one of the best parametric EQ plugins, modeled after SSL console channel strip, looks like. It has, from left to right, single knob high pass (low-cut) filter, 2-knobs low shelving section, 3 knobs low-mid peaking section, 3-knobs high-mid peaking section, 2-knobs high shelving section and in/out, phase reverse and output gain controls on the rightmost section:

With this EQ, you preset all the frequencies and Q once before the milonga starts, and then use the top four knobs as your perfect BASS BOOST, REVERB CUT, BRILLIANCE BOOST and HISS CUT controls. Brilliant, isn’t it?

If you are as impressed, as I was at my first encounter with a parametric EQ, here are your options:

- If you want the software parametric, look at this review and the comments below the article for a handful of free plugins.

- Alternatively, if you feel some Christmas itching in your wallet, check out the big boys from Waves – software emulations of some of the best available parametric EQ on this planet, including the SSL G-EQ on the picture above.

- If, however, you are, as I am, a die-hard fan of hardware knobs and switches, you can check out this rack-mounted, fully parametric EQ from Rolls

- And, finally, if you were a good boy (girl) for the whole year, and desperately searching for this perfect Christmas present for yourself look at this passive parametric EQ from Summit Audio

How to install a sound processing plugin (VST, AU, etc.)

A sound processing plugin, in VST format on Windows, or AU format on MacOS cannot run by itself, which is, pretty much hinted by its name. It requires a so called plugin host. It is quite possible that your DJ player has native support for plugins, e.g. you can load your plugin straight into the player processing chain. An incomplete list of such players is:

- Virtual DJ (Windows, MacOS, Linux)

- JRiver Media Center (Windows and MacOS)

- AIMP (Windows)

Also if you use Foobar2000 (Windows), you might try a special Foobar plugin, foo_vst, which, in turn, would allow you to load a VST plugin of your choice.

However, if none of the above applies to you, there are other ways to add plugins to your favorite player. To do that, you would require two application, one to host your plugin, and another one to route the music from your player into the plugin host. Sometimes, these two applications might be combined into one.

If you are running Windows, you can use Pedalboard 2 as your plugin host and VB Cable to connect everything together. Detailed instructions for Foobar2000 available at this forum, but you can use any other DJ player in place of Foobar.

Also, on Windows, you can use Equalizer APO, together with its Peace EQ skin, which provides you with variety of already configured graphic equalizers, including the standard 10-band EQ, and an ability to load other plugins through the editor. Using Peace EQ you can build any custom, parametric EQ which will have only the bands and the filters that you need for your tango music.

The simplest, all-in-one solution for MacOS, which only recently became available is eqMac2. It is a free, 10-band EQ that installs itself into the specified sound path, similar to Equalizer APO on Windows.

If you want to run an arbitrary plugin, Pedalboard2 also runs on MacOS with Mac-native AU plugins. For routing the signal into the Pedalboard you could use Soundflower. MacOS already has a few standard sound-processing plugins in its installation, including 10-band/31-band graphic equalizer, AUGraphicEQ, which you could immediately use for testing your sound chain or playing in the milongas. The images with 10-band and 31-band EQ settings in previous sections come straight from this plugin.

However, your best-bet for MacOS will be Audio Hijack. It will both capture the sound from any player and send it to any device, and will allow to build inside a DSP chain of any complexity. With its help, you can also save audio from any source (such as Youtube, etc.) in various formats. This is a commercial product, but it is incredibly stable, versatile, and convenient to use.

And, finally, a few words about Linux. If you are using Linux for DJ-ing, I, first of all, envy your bravery, and then, you know much more about its sound processing architecture than I do. However, if it is not the case, you should give a try to Pulse Effects package, which, past version 4.0 allows to configure its 31-band EQ to a desirable number of bands. The following Wiki page may help you with compilation, installation and configuration chores.

Personal Recommendations

Since the first appearance of this article on now defunct Yahoo DJ mail list I am often asked what specific plugins I use. So, here is the very biased and personal answer.

For DJing purposes, I strongly prefer parametric EQs over graphic EQs, and also musical, forgiving, kind of “mastering-type” EQs over aggressive, yet precise and analytic “channel-type” EQs, which pretty much shows in the choice of Crane Song Insigna over, say, excellent Great River 32 EQ or Solid State Logic 611 EQ.

In the software domain, I have tried quite a few, but for a long period of time I used only TDR Slick EQ Gentleman’s Edition, and later I switched to Red 2 Parametric EQ. All my plugins are hosted in Audio Hijack. If I have to apply some basic, yet mandatory room corrections (in situations such as boomy rooms, speakers set in club mode, inadequate mini-speakers, etc.) I also use TDR NOVA parametric EQ. If you still insist on graphic EQ, I would recommend you to wait for a substantial sale of API-560 EQ from Waves.

And yet, whenever possible, I prefer to use hardware rather than plugins. For all the experiments with the tango EQ curve, and later, in 2014-2015, I used Behringer Mini-FBQ. Then I replaced it with an amazing passive parametric FeQ-50 from Summit Audio. And finally, when my “portable” gear rack, complete with vacuum tube pre-amplifier and compressor, crossed over 25 kg mark, I have switched to 500 series format, with Crane Song Insigna passive parametric EQ in Radial Workhorse Cube enclosure.

VENUE-SPECIFIC AND ORQUESTA-SPECIFIC SOUND CORRECTION

Now that you have mastered your new EQ, successfully played a few milongas, but here is a challenge… You were invited to DJ in a new venue, and now you have a bunch of new problems – echoing room, threateningly sized sub woofers, vibrating ceiling… Could you new toy help you there? Yes, it could, if you heed the advice of Mik Avramenko, a great DJ from Kiev.

- Very live room with strong reverberation. The perception of reverberation can be somewhat reduced by cutting 200-250 Hz frequency band. Also, do not boost too much the base band in such a room.

- Typical disco-club, too much base is heard. Try a standard low-cut filter (75-80 Hz) on your mixer, or a deep cut from 80 Hz and below on your EQ.

- Something is vibrating, for instance the ceiling. Sweep through the low frequencies, from 300 Hz down. Parametric EQ is the best for this kind of job. At some frequency the vibration will die off. Again, go easy on the base band.

- Need more volume, but at higher volume it is just impossible to stay close to the speaker – the sound becomes unbearable. Here I can suggest at least two solutions:

- From DJ Mik – kill without regret 2.5 – 3.5 kHz band. If not enough, also bring down 800 Hz band.

- From the author – get into a habit of using a portable compressor, such as FMR RNC-1773, to cut the peaks in your music… However, an intelligent choice and setting up of a compressor requires a separate article.

- “Screeching” sound may appear also on lower volumes when playing certain orquestas, such as Pugliese con Moran or Rodriguez con Moreno. Again, cut 2.5 – 3.5 kHz band.

And a few more advices from the author about specific orquestas:

- Cannot play Biagi in this venue – the sound disappears completely. Rodolfo Biagi, with its unmistakeably airy sound is, probably, the only orquesta, where you should boost 1 kHz band. Just a tiny boost, for a few dB will make the sound “denser”… But it is better yet to use a compressor instead.

- I want to play a tanda of Los Mancifesta, or Tipica Rascacielos (or any other modern, yet danceable orquesta), but the contrast with the Golden Age sound is too noticeable. Is there a way to make the sound somewhat older? Indeed, to break is much easier than to make. Lower the base (150 Hz and down), and the brilliance (from 5-8 kHz and up), but try not to overdo it.

- Screeching metallic sound is clearly heard when controlling the brilliance with 4 kHz band. This effect may appear only in certain venues, but if it does, once again, use the scissors trick. Bring slightly down the closest to 4 kHz lower band, namely 2 kHz.

And finally, the most important advice from DJ Mik, verbatim:

Do not overdo it, ever! Liberal application of EQ can easily distort the timbre and make the things much worse than they were. My rule of thumb is: if I cannot unambiguously hear the improvement in the sound, produced by my EQ, I simply turn the EQ off. In some cases, just bringing down the volume can “fix” many audible problems.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Big thanks to:

- Arseny Persik of Sour Peach Studios for showing me, on my own Behringer EQ, how virtually any record can be manipulated to an order of magnitude better sound, and for being an endless source of information on any subject of sound engineering

- DJ Mik Avramenko, from Kiev, for the detailed feedback and a bunch of advices on the venue sound control

- Gabriel Valiente, the author of Tango Encyclopaedia, for reporting the first success with my technique, in less than 24 hours after this article was posted on Tango DJ mail-list

SOME USEFUL LINKS

- Interactive frequency chart: all you wanted to know about relations between frequencies, notes, and instruments

- Psycho-acoustics: a gentle introduction to the vast subject of psycho-acoustics

- Disc Recording Equalization Demystified: detailed explanation of vinyl RIAA equalization curve and earlier, non-standardized shellac recording curves, with the physical reasons behind them

Version 3.10

Last updated on 2020/02/02

Thanks! This was awesome!

LikeLike

Many thanks for the content, any idea of what would be the best equalizer settings among iPhone choice ? More classical, jazz, accoustic, voice ?

LikeLike

For any music recorded in the 60s and later I’d recommend to invest into a pair of good headphones, and then to keep your EQ either perfectly flat, or maybe with a slight “smile” for low volume. Less is more.

LikeLike

Many thanks !

LikeLike

Very interesting article, a must read for tango DJs!

LikeLiked by 1 person

greetings. After living for the past 35 years in Argentina, having loved tango for the past 57 years or so, and being an audiophile for some 50 years and furthermore collecting records a lifetime, I thoroughly enjoyed reading this eq page and the tango labels one. I believe I have plenty to share and will do so shortly. Most probably I will be writing to the email adress offered (the jens ingo one) and we will see what comes out of this. Just allow me to set this tablet aside and rig a healthy computer with a decent keyboard…..

LikeLike

Thank you, Hugo. I’d be very interested to see your writings.

LikeLike

Excellent and very kind to share. Respects.

LikeLike

This was super helpful! I have lots of recordings from the 1920-1950s and I hate how they sound so flat and quiet when compared to other music types. These settings really added dimension to my old songs! I feel like I am listening to them the first time. Thank you so much for the in depth and clear description.

LikeLike

Thank you very much for sharing your knowledge!! Looking for something like this long time ago… Integrating in my workflow.

LikeLike

Thank you, El Espejero, for the great article. I have a question on Red 2 EQ. What settings are you using? Are they: „Low shelf” for bass boost, ”low mid” for the reverb, „high mid” for the brilliance and „high shelf” for the hiss? What frequencies on knobs? The same you described in the article? And what Q factors? Thank you.

LikeLike

Thank you a lot. This is exactly, what i needed!

LikeLike